All great civilizations of history have experienced revolutions and the tides of war. One of the greatest civilizations of all time- the Roman civilization, was no different.

It saw its fair share of revolts and battles between various groups under different leaders over a period of over a hundred years.

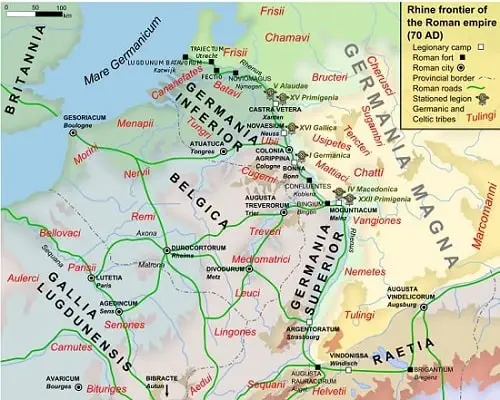

The Batavian Revolt is one such occurrence. Between AD 69 and 70, the Batavi Revolt transpired in the Roman region of Germania Inferior.

It was a revolt to win over the Roman Empire led by the Batavi, a tiny but militarily formidable Germanic tribe who lived in Batavia, on the Rhine’s estuary.

They were quickly joined by Celtic clans from Gallia Belgica as well as certain Germanic tribes.

The Batavi along with the adherents managed to humiliate the Roman army, with the loss of a few Roman legions, under the command of their hereditary ruler Gaius Julius Civilis, an honorary soldier in the Imperial Roman battalion.

Following these early victories, a huge Roman force commanded by the Roman general Quintus Petillius Cerialis subdued the insurgents.

Following peace discussions, the Batavi surrendered to Roman sovereignty once more but were compelled to endure onerous arrangements and a cohort entrenched at Noviomagus.

Who were the ancient Batavi people?

Content

The Batavi were an indigenous Germanic tribe who resided near the modern Dutch Rhine delta in the area known to the Romans as Batavia from the second half of the first century BC to the third century AD.

What is Batavia called now?

Ancient Batavia is modern-day Jakarta.

What happened to the Batavi people?

The Batavi were still recorded in 355 during the time of Constantius II (317 – 361) when their island had already been ruled by the Salii, a Frankish tribe that had sought Roman protection there in 297 after being driven out of their own homeland by the Saxons. It has been assumed that they amalgamated with the Salii shortly before or after being evicted by another tribe (perhaps the Chamavi) and shared their later journey to Toxandria.

History of the Batavi

The Batavi, an ancient part of the Germanic Chatti ethnic group, was relocated to the area between two rivers, Waal and Old Rhine.

Despite conceivably fertile fluvial sediments, their land was mainly cultivable, comprising Rhine delta wetlands.

As a result, the Batavi populace it could sustain was limited to 35,000 people at the time.

A mighty tribe, adept at horseback riding, boating, and swimming made them outstanding soldiers.

They furnished a significant number of soldiers to the Julio-Claudian auxilia in exchange for the rare privilege of immunity from tributum: 1 ala and 8 cohorts.

Likewise, they also supplied the majority of Emperor Augustus’ specialized unit of Germanic warriors that existed until AD 68.

The Batavi auxilia had around 5,000 men, meaning that during the time of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, more than half of the males of Batavi with an average age of 16 may have been enrolled in the auxilia.

So, despite accounting for only around 0.05 percent of the Empire’s entire population in 23 AD, the Batavi furnished about 4 percent of auxilia as the whole.

The Romans considered them the finest and fiercest (fortissimi, validissimi) of their auxiliary forces if not all of their troops.

They had also mastered a unique skill for swimming through rivers while donning full armor and weaponry while in Roman service.

Likewise, Gaius Julius Civilis was a Batavi royal prince and the military officer of a Batavi cohort. He alongside the 8 Batavi cohorts had served as an essential part in the Roman conquest of Britain in 43 AD, having served in the Roman army for 25 years.

However, by 69, Civilis, the troops, and the populace of Batavi had become wholly dissatisfied with Rome.

In 66, the Batavi soldiers were removed from Britain, when Germania Inferior’s governor imprisoned Civilis along with his brother on spurious charges of mutiny.

The governor commended the brother’s execution and transported Civilis to Rome in chains to be judged by the Roman Emperor Nero.

In 68 AD, the army led by Hispania Tarraconensis’s governor overthrew Nero during which Civilis was in the prison waiting for his trial.

The overthrown led Nero into committing suicide which brought along the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and the crowing of Galba as the new Emperor.

Civilis was acquitted of the treason allegation, and he was made free to go back home.

However, the harshness of the Roman recruiting centurions guilty of many incidences of assaulting Batavi boys sexually exacerbated the Batavi homeland’s already simmering anger.

Cause of the Batavi Revolt and Uprising

Civilis, the leader of auxiliary troops of the Batavian, was assigned to the Rhine legions in the summer of 1969. He was familiar with Roman military techniques, which provided him with ideas to overcome them.

The initial task was to build up a ruse, and Civilis instigated a mutiny outside Batavia. The Cananefates were a tribe that lived betwixt the Batavians and the North Sea.

Civilis’s revolt entices the unknown, but the Cananefates, commanded by their chief Brinno, besieged many Roman forts, notably Traiectum (Utrecht).

As a result, the Romans were caught by surprise because most of the forces in Italy were battling in the civil conflict. Flaccus, leader of the Rhine legions, dispatched reinforcements to manage the situation.

As a result, the Romans suffered yet another defeat. Civilis also took on the role of insurrection strategist and beat the Romans at present Arnhem.

Flaccus dispatched the V Alaudae and XV Primigenia armies to combat the insurgents. They were accompanied by three auxiliary groups, including a Batavian cavalry unit led by Claudius Labeo, a renowned adversary of Civilis.

The conflict took place in the vicinity of current Nijmegen. The Batavian troop fled to their compatriots, undermining the Romans’ already shaky spirit.

The Roman army was defeated, and the legions were forced to withdraw to Castra Vetera, their campsite (modern Xanten).

The Batavians were self-sufficient and held the advantage at this point. Even Vespasian, battling Vitellius for the Empire, applauded the uprising that prevented his adversary from summoning the Rhine troops to Italy.

Civilis was on his approach to becoming king, and the Batavians have assured autonomy.

The Siege of Castra Vetera (Defeat of Two Roman Legions by the Batavi)

However, for unclear reasons, this was insufficient for the Batavians. Civilis opted for vengeance and vowed to eradicate the two Roman legions.

The timing was excellent, with the civil conflict of the Year of the Four Emperors at its height, Rome needed some time to mount an efficient retaliation.

Furthermore, Vitellius’ army’s eight Batavian auxiliary regiments were on their way home and might easily be convinced to join the insurrection for a sovereign Batavia.

This was a crucial reassurance. Aside from being veteran troops, their numbers outnumbered the combined Roman forces positioned in Moguntiacum (Mainz) and Bonna (Bonn).

Civilis launched the assault of Castra Vetera, the barracks of the 5,000 roman soldiers of V Alaudae and XV Primigenia, in September 69.

The camp was very advanced, packed with resources and well, with the facade of mud, cinder block, wood, turrets, and a double ditch.

As such, Civilis resolved to starve the men into submission after several failed efforts to seize the camp by force.

Meanwhile, Flaccus chose to wait for the outcome of the Italian conflict. Galba had recently condemned the Rhine legions for their conduct against the insurgent Vindex of Gallia Lugdunensis.

Vespasian was conquering the war, and Civilis was assisting him in becoming Emperor by stopping at least two troops loyal to Vitellius imprisoned in Xanten from arriving at his aid.

Flaccus and his commanders chose to wait for commands rather than risk a subsequent military mistake.

However, even after learning of Vitellius’ loss, Civilis maintained the siege. He was not warring for Vespasian, but for Batavia. Flaccus began planning an offensive to save the trapped troops.

Civilis would not delay until they were adequately equipped before launching a surprise attack. His finest eight cavalry legions assaulted the Romans in Krefeld on December 1.

The Roman army won the battle, which annihilated the Batavian cavalry. However, their losses were enormous.

Civilis withdrew the siege and vowed to attack Moguntiacum, anticipating that the Romans would arrive at Castra Vetera.

Consequently, the Romans were duped and hastened to their home headquarters in Germania Superior to save it. They learned about Vespasian’s ascent to the throne in Moguntiacum.

Flaccus then chose to commemorate the occasion by awarding wealth to the legions.

However, these legions had previously been loyal to their old ruler, Vitellius, and this gesture of charity was perceived as an insult.

Flaccus was assassinated, and his second-in-command defected, throwing the Roman army in disarray.

Civilis sensed an opportunity and, before the Romans could react, his men assaulted Castra Vetera yet again.

The Swell of the Batavi Rebellion

The odds were stacked against the rebels when the year 70 began. Two legions remained trapped at Castra Vetera, while the remainder of the Roman force was insufficient to deal with the revolt.

Aside from the Batavian insurrection, the Trevirans and Lingones proclaimed Gaul’s sovereignty. The rebel emperor, Julius Sabinus, convinced the I Germanica and XVI Gallica to support him.

The situation in Castra Vetera was dire. Provisions had run short, and the beleaguered troops were surviving by eating horses and mules.

With little hope of relief in sight, the leader of the army, Munius Lupercus, chose to surrender.

If the legions left the camp to be plundered by the insurgents, they were assured peaceful conduct. Weapons, artillery equipment, and gold were all left to be looted.

V Alaudae and XV Primigenia proceeded out of the camp but were attacked and killed by Germanic warriors after only a few kilometers.

The commander and critical officers were sold as enslaved people and handed as a gift to Veleda, the prophetess who foresaw the Batavians’ ascendancy.

Following this achievement, Civilis traveled to Colonia Agrippina (Cologne) and established a camp there.

He spent the following few months persuading other clans from northern Gaul and Germania to participate in the uprising.

Roman Retaliation against the Batavi Revolt

Germania’s insurrection was now a severe menace to the Empire. Two legions had been lost, while two others (I Germanica and XVI Gallica) were under insurgent hands.

This could not continue for much further. Vespasian determined to intervene as soon as he had command of the Empire and the circumstances in Italy.

Quintus Petillius Cerialis, a close family member and accomplished general, was appointed head of the punitive force. To avoid a defeat, a large army was recruited.

The legions VIII Augusta, XI Claudia, XIII Gemina, XXI Rapax, and the newly recruited II Adiutrix were dispatched to Germany right away.

In addition, the legions I Adiutrix and VI Victrix from Hispania and XIV Gemina from Britannia were also dispatched.

Meanwhile, Civilis attempted to assault the Roman army from his hometown of Batavia for a while in a succession of attacks by land and, with the assistance of his flotilla, in the rivers Waal and Rhine.

Civilis seized the Roman fleet’s flagship during one of these raids. This was a disgrace that warranted retaliation. Cerialis chose to invade Batavia rather than wait any longer.

On the flip side, Rome was highly involved with massive military endeavors in Judea during the First Jewish–Roman War at the start of the uprising.

The siege of Jerusalem, which began in April 70 AD, was lifted by early September, and the conflict was effectively done.

When Civilis learned that Jerusalem had lost and recognized that Rome would now use all of its forces against him, he made a truce.

Peace discussions were then held. A bridge was built across the Nabalia River, where the warring factions approached from both sides.

The general terms of the treaties are obscure, but the Batavians were required to reaffirm their allegiance with the Roman Empire and mobilize eight additional auxiliary cavalry units.

Nijmegen, the Batavian capital, was razed, and its residents were ordered to reconstruct it a few kilometers downstream, in a defensive position. Furthermore, X Gemina would be positioned nearby to ensure peace.

However, Civilis’ fate, the hero of the revolt, is unknown.

Conclusion

The relatively small yet intimidating Batavian tribe inflicted Rome’s most devastating defeat. What’s more, it wasn’t just a defeat; it was utter destruction, with more than two entire legions of the Roman Army gone.

The Batavian revolt was such a severe threat that the Roman emperor had to quell pressing war elsewhere to gather troops and defeat Civilis and ensure peace treaties were operated.

The Revolt of the Batavia will forever be engraved within the minds of the people of modern-day Netherlands as its historical impacts remain in contemporary times.