Ancient Roman Literature, Artworks, myths, archaeological relics, and inscriptions provide evidence of ancient Rome’s sexual attitudes and habits.

These pieces of evidence show that license for sexuality was one of the significant features of Ancient Rome. However, as per Provençal and Verstraete’s note, this viewpoint is a Christian assessment.

They mentioned that sexuality in Ancient Rome could not ever get great publicity in the Western part since the emergence of Christianity.

Thus, it is associated with the licensing of sexuality and abuse in the popular consciousness and society.

However, the ancient social values and norms affecting private, public, and military life did not eliminate sexuality as a concern.

Together in the Republican and Imperial periods, pudor, meaning modesty and shame, was one of the controlling forces in behavior, along with legal restrictions on specific sexual crimes.

The public authorities of the censors who evaluated an individual’s social rank had the authority to outthrow the individual from orders of equestrian and senatorial if found guilty of sexual impropriety.

Not to mention, in patriarchal Roman society, the ones who could manage people belonging to the lower class in wars, relations involving sexual activities, and politics were considered to have better masculinity.

Homosexuality, Prostitution, and Sexual Attitude in Ancient Rome

Content

Some sexual views and actions in Roman civilization were notably different than the societies belonging to Western civilization that existed after some time.

Roman religion emphasized sexuality as a part of state wealth. People sometimes changed to magics or private religious practices to improve their reproductive health and daily activities involving erotic events.

Similarly, prostitution was also considered legal, open to the public, and ubiquitous. Besides, paintings depicting pornography were found in the art gallery of well-to-do upper-class families.

In like manner, men getting attracted to male and female that has reached teenage was regarded as natural and unremarkable.

Pederasty was also tolerated if one of the partners, mainly the younger one, did not belong to the category of a freeborn Roman.

Furthermore, both heterosexual and homosexual were not the fundamental dichotomies in Roman thinking on sexuality.

No moral condemnation was leveled at the guy who engaged in sexual acts with men and women of a lower class. However, his acts should not reveal flaws or excesses.

Similarly, if the act was proven to perceive any effeminacy, particularly in political language, sex in restraint with the male sex worker or a slave was not considered immoral or corrosive.

It was considered only if the male took the active role rather than acting as a receptor.

Hypersexuality, on the other hand, was ethically and medically condemned in both genders. Moreover, women were subjected to a harsher moral code.

Although same-sex relationships between two females are infrequently documented, women’s sexuality is loathed throughout Latin literary works.

Likewise, a paradigm around the 20th Century examined Roman sexuality through the lens of a binary model famously known as penetrator–penetrated.

However, this approach has limits, particularly regarding sexual expressions among Roman citizens.

Even the term sexuality has been questioned in the ancient society of Rome.

Transvestism, Gender Roles, and Determinants of Sexuality in Ancient Rome

During the Republic, a Roman citizen’s civic Liberty (Libertas) was characterized in part by the right to keep his body free from physical compulsion.

The notion included both corporal punishment and sexual abuse.

Among the active virtues was a virtue, or “valor.” This notion was regarded as something that made a man most fully a man (vir).

Moreover, Roman ideas of masculinity were thus based on taking an active role. This idea was also the prime direction of male sexual activity for Romans.

Likewise, the drive to action could be most vividly expressed in a dominating ideal representing the hierarchy of Roman patriarchal society.

As such, the “conquest attitude” was a component of a “cult of virility” that impacted Roman homosexual activities.

Moreover, an emphasis on dominance led scholars in the late 20th and early 21st centuries to perceive gestures of Roman male sexuality in aspects of a “penetrator-penetrated” binary model.

To elaborate, allowing himself to be penetrated jeopardized the male’s liberty as a free citizen and his sexual integrity.

In other words, a freeborn Roman man was expected and excusable to crave sex with male and female partners as long as he took the dominant role.

Likewise, tolerable artifacts of desire were women of any legal and social prestige, male prostitutes, or enslaved men.

But sexual practices outside marriage were restricted to enslaved people and prostitutes, or, less frequently, a concubine or “kept woman.”

Similarly, populares were seen as defenders of the people and were frequently referred to as Rome’s “democratic” party.

In contrast, the optimates were seen as a conservative elite of aristocrats and were accused of effeminacy.

Mark Antony, Julius Caesar, Clodius Pulcher, and Catilinarian conspirators were mocked as effeminate around the ending years of the Roman Republic.

They were seen as beautiful men who had maintained themselves pretty well. This led other interested males to be attracted to them for the sole purpose of sex.

Simultaneously, they were also accused of being womanizers or possessing an excellent level of sex appeal.

Additionally, cross-dressing also exists in Roman literature and art as a mythological motif. A popular narrative is that of Hercules and Omphale switching roles and attire.

Roman literature also depicted cross-dressing as the ecclesiastical investiture, infrequently or ambiguously presented as transvestic fetishism.

Not to mention, gender ambiguity was also a feature of the Galli priests of the goddess Cybele. Their ritual dress comprised women’s garments.

Because they were supposed to be castrated in the emulation of Attis, they are also sometimes regarded as a transgender priesthood.

Catullus explores the difficulties of gender identification in Cybele’s religion and the Attis story in Carmen 63, one of his longest poems.

Hermaphroditism and Androgyny in Ancient Rome

In modern English, the term “hermaphrodite” is used in biology but has negative connotations when referring to those born with physical traits of both sexes.

But, in antiquity, the image of the so-called hermaphrodite was a prominent focus of gender identity concerns.

In ancient Rome, the hermaphrodite was a “violation of societal boundaries, particularly those as crucial to daily existence as male and female.”

A hermaphroditic birth was considered a prodigium in the old Roman religion. It was an occurrence that signaled a disruption in the pax deorum, Rome’s pact with the gods.

As such, a hermaphrodite had to be classified as either male or female under Roman law. No third gender was recognized as a legal category.

Likewise, in a mythical Roman legend, Hermaphroditus was a lovely youngster who was the son of Hermes (Roman Mercury) and Aphrodite (Venus).

He had been fostered by nymphs, like many other divine beings and heroes. But proof that he earned cult devotion among the Greeks is scant.

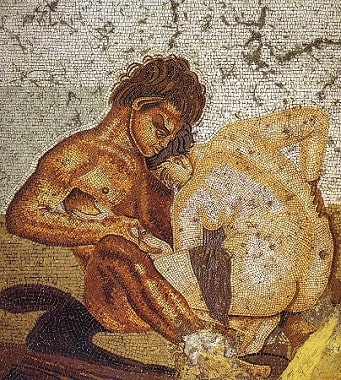

Hermaphroditus depictions were prevalent among the Romans. The dramatic scene in paintings frequently causes the viewer to “double-take” or reflect on the notion of sexual frustration.

Hermaphroditus is also frequently seen with one of the fairies’ satyr, a figure of bestial sexuality infamous for forcing an unwary or sleeping victim to non-consensual intercourse.

The satyr in scenarios with Hermaphroditus is also usually shown as being astonished or horrified.

Similarly, Macrobius mentions a masculine form of “Venus” (Aphrodite), who was worshiped in Cyprus. She dressed in women’s attire and had a beard and male genitals.

Worshippers of the deity were also cross-dressing. Men wore women’s garments, and women wore men’s.

Laevius, a Latin poet, also wrote of worshiping “nurturing Venus,” whether female or masculine (sive Femina sive mas). Aphroditos was another name for the figure.

In the attitude anasyrmene, she is depicted from the Greek verb anasyromai, “to pull up one’s garments,” in various surviving examples of Greek and Roman sculpture.

The love goddess raises her robes to display her masculine attribute, male genitalia, a gesture with apotropaic or magical power in the past.

The Narrative of Male and Female Sexuality in Ancient Rome

Romans viewed female sexuality as one of the foundations for social order and success. It was so because of the Roman priority on family.

Female citizens were expected to undertake their sexuality within marriage. Females rewarded them for their sexual fidelity (pudicitia) and fecundity.

Augustus also gave special honors and privileges to women who gave birth to three children.

Likewise, Ancient Romans viewed the discipline of female sexuality as necessary for state stability.

This notion is exemplified most dramatically by the Vestal virgins and their utter and absolute importance of virginity.

A Vestal who broke her pledge was encased alive in a procedure resembling a Roman funeral. Her lover was killed.

In crisis situations for the Republic, female sexuality, whether disordered or exemplary, frequently impacts state religion. Augustus’ moral legislation was also centered on exploiting women’s desires.

As with men, free women who exhibited themselves sexually, such as prostitutes and performers, or made themselves available to anybody were denied legal safeguards and social respectability.

Nevertheless, Roman men were allowed to have intercourse with lower-status males without fear of losing their masculinity or even enhancing it.

Those who adopted the receiving role in sex acts, also known as the “passive” or “submissive” role, were regarded as weak and effeminate, regardless of their partner’s sex.

But having sex with males in the active position was proof of one’s masculinity.

Although Roman law did not acknowledge marriages between two males, some male partners celebrated traditional marriage rites throughout the early Imperial period.

Apart from steps to protect citizens’ liberty, the prosecution of homosexuality as a general criminal began in the third century. Male prostitution was prohibited by Philip the Arab, a Christian sympathizer.

Likewise, passive homosexuality was also punishable by burning under the Christian Empire by the end of the fourth century.

The punishment for a “male coupling like a woman” under the Theodosian Code was “death by the sword.”

Similarly, hetairistria (“courtesan” or “companion”), tribas, and Lesbia are Greek words for a woman who loves intercourse with another woman.

Latin words for such also include loanword tribas, fricatrix (“she who rubs”), and virago. In the Roman literature of the Republic and early Principate, however, references to sex between women are rare.

Nonetheless, sources for same-sex encounters among women are more available throughout the Roman Imperial age.

Many Roman writers considered this notion more decadent than the Republican period.

It was seen in forms of love charms, medical writing, writings on astrology, dream interpretation, and other sources.

Sex and Marriage in Ancient Roman Society

Because males could have sexual encounters with relative impunity outside of marriage, historians commonly claimed that pleasurable sex was not an obligation of Roman marriage.

Nonetheless, sexual intimacy between a husband and wife was a private topic rarely discussed in the literature.

However, the epithalamium, a type of poetry that celebrated a wedding, was an exception.

In like manner, although it was considered a source of pride for a woman to be univira, or to have only married once, there was no stigma linked to divorce.

Remarrying quickly after a divorce or the death of a husband was normal, even expected, among the Roman elite. This was because marriage was regarded as correct and natural for adults.

Similarly, although widows were typically expected to wait ten months before remarrying, a pregnant lady was not forbidden from accepting a new husband.

She could do so as long as the paternity of her child was not in question for legal reasons.

If a first marriage ended in divorce, women could appear to have had more influence in arranging successive marriages.

As such, while having children was the primary objective of marriage, other social and familial relationships were strengthened.

It included personal friendship and sexual satisfaction between husband and wife, as seen in marriages relating to women past childbearing age.

Conclusion

Sex, sexuality, and gender norms remain a severe issue in today’s political and social landscape. These subjects garner discussions that center on a variety of crucial issues.

From freedom of expression to comfort, biology, and culture, among many others, the narrative of sex, sexuality, and gender includes a vast array of branches that are too many to list.

However, the existence of these concerns is not new, as each society must build its norms and mores about these issues.

As such, the classical Greco-Roman culture that emerged throughout the western Mediterranean was counted among the most significant to impact the creation of current western civilizations.

Their perspectives on these topics are no different either.

While nothing today fully matches the classical viewpoints, it is still necessary to trace the origins of these opinions to follow their progression to modern notions.