Today’s Rome, though not the capital of a vast empire still remains globally significant with over 1 billion people viewing considering it the center of the Roman Catholic faith.

Rome’s eventual admission of Christianity, after years of apathy and persecution, influenced the majority with the new hope and faith.

Saint Peter was persecuted along with numerous others, during the time of the assassination and persecution of the Christian by the then Emperor Nero.

However, in 319 AD, Roman Emperor Constantine started constructing the cathedral over the grave of Saint Peter to make it his Basilica.

Ancient Rome was an intensely religious culture from its inception, where religious, offices and political offices coexisted.

Julius Caesar initially held the highest position amongst the priest and was honored as Pontifex Maximums. He, later on, landed on being chosen as Consul, the highest Republican political post.

Similarly, the Romans also worshiped many gods, some of which were the counterpart of the Ancient Greeks deities, and the city of Greek was replete with temples where the power of the gods and goddesses was placed according to sacrifice, ritual, and festival.

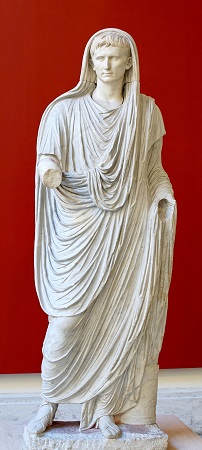

In fact, at the top of his powers, Julius Caesar achieved god-like status and was venerated after he died. Likewise, Augustus, the successor of Caesar, also embraced this practice.

Moreover, even though this apex to this heavenly status occurred after his death, the Emperor was still a deity to the Romans. However, this idea was later found exceedingly offensive by the Christians.

With the expansion of Rome, it confronted new religions, that had to be tolerated by the majority and adopted by some. On the other hand, some were picked out for persecution, mainly due to their nature that was not accepted by the Romans and was considered different than all the Romans.

The religion of Bacchus, a Roman embodiment of the Greek god of wine, was suppressed for alleged orgies.

At the same time, the Roman forces wiped out all the Celtic Druids as the procedure of the inhuman acts of sacrificing humans.

Even the Jews were oppressed, especially following Rome’s protracted and violent occupation of Judea.

So then, how did Rome come to embrace Christianity which subsequently led to Rome becoming one of the most venerated Christian capitals in the modern world?

Below is a timeline of ancient Roman religion and its consequent transpiration into Christianity and how the two differ.

What made Christianity distinct from Roman religion?

Content

The Roman religion worshiped several gods and regarded the Emperor as a god. Whereas Christianity believes in a single God and criticized many Roman beliefs and customs.

What was the origin of Christianity in the early Roman Empire?

In 313 AD, Emperor Constantine enacted the Edict of Milan, which recognized Christianity as the Roman Empire’s official religion; ten years later, it had become the central religion Empire.

How did the Romans react to Christianity?

During the first two centuries CE, Christians were periodically persecuted (officially punished) for their beliefs.

However, the official policy of the Roman state was to overlook Christians unless they blatantly challenged imperial authority.

Religion in Ancient Rome

The Romans were religious, and their success as a world power was attributed to their collective piety (pietas) in keeping good connections with the gods.

The Romans were noted for honoring various deities, which earned them the ridicule of early Christian polemicists.

From the commencement of the historical period, the inclusion of Greeks on the Italian peninsula shaped Roman culture, establishing various religious rituals that became as vital as the cult of Apollo.

In like manner, the Romans also sought common ground between their primary gods and those of the Greeks (interpretatio graeca), incorporating Greek stories and iconography for Latin literature and Roman art.

The Etruscan religion had a significant impact on ancient Roman religion, notably on the practice of augury.

Legend has it that most of Rome’s religious institutions may be traced back to its founders, particularly Numa Pompilius, the Sabine second king of Rome who dealt directly with the gods.

As the Roman Empire grew, migrants to Rome took their native cults with them, most of which became widespread among Italians.

Christianity was ultimately the most effective, becoming the official state religion in 380. Religion was a core component of everyday life for ordinary Romans in ancient times to elaborate on this notion.

Each home had a domestic shrine where prayers and libations were dedicated to the family’s domestic deities.

The city was peppered with neighborhood shrines and sacred sites such as springs and trees. The Roman calendar was also designed to accommodate religious observances.

Eastern Influences on Ancient Religion in Rome

There was a concerted effort to restore previously believed belief systems among the Roman populace during Augustus’ reign. By this point, these once-held values had been corroded and met with skepticism.

The imperial order placed a premium on commemorating outstanding men and events that led to the doctrine and practice of divine kingship.

Post-Augustus Emperors held the role of Chief Priest (Pontifex Maximus), merging political and ecclesiastical power under one title.

Another outcome of eastern hegemony in the Roman Empire was the formation of mystery cults, which worked through a hierarchical comprising of the conveyance of knowledge, virtues, and authority to those inducted through secret rites of passage.

The most renowned of these was the Mithras cult, which was especially popular among soldiers and was based on the Zoroastrian deity Mithra.

Pessimism with earthly goods, an emphasis on death, and a preoccupation with the hereafter became a prevalent motif among the eastern secret religions present in Rome.

These characteristics later led to the allure of Christianity, which was often seen as a mystery religion in its early phases.

The Assimilation of Cults

The Roman Empire grew to include various peoples and cultures. In general, Rome pursued the same inclusionist policy that had recognized Latin, Etruscan, and other Italian peoples, cults, and deities as Roman.

Those who recognized Rome’s sovereignty kept their cults and religious calendars separate from Roman religious law.

Likewise, Sabratha, a newly formed municipality, constructed a Capitolium near its existing temples to Liber Pater and Serapis.

Autonomy and concord were official policies, but new foundations established by Roman citizens or their Romanized allies were likely to adhere to Roman cultic patterns.

Romanization provided different political and practical benefits, particularly to local elites. The extant effigies from Cuicul’s 2nd century AD forum are of emperors or Concordia.

By the middle of the first century AD, Gaulish Vertault abandoned its native cultic sacrifice of horses and hounds in favor of a nearby newly created Romanised cult.

By the end of the century, Sabratha’s so-called tophet was no longer in use.

Dedications to Rome’s Capitoline Triad by Colonial and subsequently Imperial provinces were a logical decision, not a centralized legal mandate.

The splendid Alexandrian Serapium, the temple of Aesculapius at Pergamum, and Apollo’s holy grove at Antioch were all major cult centers to “non-Roman” deities.

Traders, legions, and other travelers also brought cults from Egypt, Greece, Iberia, India, and Persia. Cybele, Isis, Mithras, and Sol Invictus cults were especially important.

Some of these were initiatory faiths with profound personal importance, similar to Christianity in that regard.

Judaism in Ancient Rome

Jews and Judaism were permitted at Rome by diplomatic contract with Judaea’s Hellenised elite for at least a century before establishing the Augustan principate.

Diaspora Jews shared many characteristics with the predominantly Hellenic or Hellenised communities that surrounded them.

There are scant records of early Italian synagogues, but one was dedicated at Ostia during the mid-1st century BC, and numerous more are known during the Imperial period.

The acceptance of Judaea as a client kingdom in 63 BC extended the Jewish diaspora; in Rome, this resulted in increasing official investigation of their faith.

Julius Caesar recognized their synagogues as genuine collegia. Several thousand Jews lived in Rome by the time of the Augustan era.

In some instances, Jews were legally excluded from official sacrifice throughout several eras of Roman administration.

To Cicero, Judaism was a superstitio, but to the Church Father Tertullian, it was a religio licita (an officially permitted religion) in opposition to Christianity.

The Roman Empire and Christianity

The Romans discovered early Christianity as an irreligious, new, defiant, even atheistic sub-sect of Judaism. It purported to repudiate all forms of religion and was thus superstitious.

By the conclusion of the Imperial period, Nicene Christianity was the only permitted Roman religion; all other religions were considered heretical or pagan superstitions.

In 64 AD, preceding the Great Fire of Rome, Emperor Nero accused Christians of being easy scapegoats, and they were later persecuted and executed.

The Roman state’s stance toward Christianity was one of persecution from then on.

“Contemporaries were inclined to decode any problem in religious terms” during the many Imperial crises of the third century, regardless of their commitment to particular practices or belief systems.

Christianity garnered its conventional base of assistance from the powerless, who appeared to have no theological investment in the Roman State’s well-being and threatened its survival.

The majority of Rome’s aristocracy practiced various versions of inclusive Hellenistic monism.

Neoplatonism, in particular, integrated the miraculous and austere within a typical Graeco-Roman cultic framework.

Christians considered these behaviors sinful and a significant source of economic and political instability.

Following religious disturbances in Egypt, Emperor Decius issued a proclamation requiring all subjects of the Empire to actively seek the benefit of the state through observed and verified sacrifice to “ancestral gods” or face a penalty: only Jews were excused.

Christianity and Emperor Constantine

Constantine I’s conversion put a stop to Christian persecutions.

Constantine effectively reconciled his function as an agent of the pax deorum with the influence of the Christian priesthoods in judging what was auspicious – or orthodox – in ancient Roman terms.

The Edict of Milan (313), which redefined Imperial doctrine as one of mutual tolerance, was issued.

Constantine had won under the signum (sign) of Christ, so Christianity was formally recognized alongside old religions, and from his new Eastern city, Constantine could be viewed to symbolize both Christian and Hellenic religious values.

He also enacted legislation to safeguard Christians from persecution and supported the construction of churches, including Saint Peter’s Basilica.

He formally abolished – or attempted to abolish – blood sacrifices to the genius of live emperors.

Still, his Imperial iconography and court rituals surpassed Emperor Diocletian’s in their supra-human exaltation of the Imperial hierarch.

Christianization in the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire’s Christianization began around AD 30–40, slowly and with difficulty, in the Roman province of Judaea in the territory of Palestine.

Beginning with fewer than 1000 people, Christianity expanded at an estimated annual compound rate of approximately 3.4 percent, attaining approximately 200,000 people by the end of the 2nd century, half of the Empire’s citizenry by 350, and ultimately overarching the majority of its 6–7 million people in the 5th century.

Christianity and the traditional Roman religion were found to be irreconcilable.

Since the 2nd century, the Church Fathers have labeled the many non-Christian religions practiced across the Empire as “pagan.”

Some researchers believe Constantine’s efforts contributed to Christianity’s rapid growth, although many modern scholars disagree.

Constantine’s distinct brand of Imperial orthodoxy did not outlive him. Following his death in 337, two of his sons, Constantius II and Constans, seized over the Empire and re-divided their Imperial inheritance.

Constantius was a member of the Arian sect, but his brothers were Nicene Christians.

Conclusion

Ancient Christianity developed as a part of Roman society, and as a result, Christianization was not a one–way street.

Some features of its cradle culture were absorbed by Christianity, which corresponded with changes within Graeco-Roman polytheism.

How much Christianity brought about a shift in polytheism (also known as paganism) and how much polytheism attributed to changes in Christianity are both concerns of Christianization.

According to Roger Bagnall, the advent of Christianity came at the expense of paganism, at least in part.

This story has typically been portrayed in competition and conflict between them.

However, Graeco-Roman polytheism was not a unified entity, nor were its various manifestations universally antagonistic to Christianity.