Roman made countless contributions to areas that impacted world history. Some of the major contributions are in the areas of philosophy, literature, and art.

However, their contemporary idea regarding government counts as the most precious contributions to the world, both ancient and the future.

While the modern concept of democracy arose from political conflicts in Athens, it was realized during the periods of the Republic of Rome and the Roman Empire, despite the emperor’s frequent meddling.

Although democracy’s modern idea has evolved significantly, its origins must be traced back to the eternal city of Rome.

What were the three main parts of the Roman government?

Content

The three primary parts of the Roman government comprised the Senate, the Consuls, and the Assemblies.

How did the government promote family in ancient Rome?

The promotion of family in ancient Rome took the form of Emperor Augustus’ objecting to the decline of Roman morals and, in 18 BCE, enacting a series of laws to promote marriage, marriage fidelity, and childbirth.

What was the social class structure like in the Roman Empire?

Ancient Roman society was primarily divided into the upper-class Patricians and the working-class Plebeians.

The shift from Monarchy toward Representation

People of Rome realized after years of living under the unforgiving constraint of the Roman King that they were required to fight and protect themselves from one individual’s authority and potential tyranny.

The republic’s and later empire’s true sovereignty or imperium was split among three main elements: famous assemblies, consents and advice from the Senate, and non-hereditary magistrates.

However, in Ancient Rome – especially during the early days of the Republic of Rome, people belonging to the families of the landowners, patricians, or the privileged were the only ones to enjoy authority.

While the plebeians, who comprised the majority of the city’s inhabitants, hardly were given rights but this imbalance of power distribution did not last for a long period of time.

The Senate

Despite later parliamentary assemblies, the Senate of Rome had very little legislative authority, with popular groups wielding that power.

Initially, the Senate wielded a special power known as the auctoritas. This power was an indirect version of the executive power that was basically meant for the patricians.

While it lacked legal authority, it exerted considerable influence as a part of the advisory council to consuls and emperors.

Representatives of this orthodox body were uncompensated and were made to serve until their final verdict of being guilty of either private or public wrongdoing.

Likewise, Senators were barred from engaging in business transactions such as international trading and bank-related works.

Similarly, the Roman Senate was mainly the realm of the affluent for the majority of its establishment.

And while its capacity to shape leadership dwindled throughout time, particularly during the rule of the emperors, participation in this venerable organization shifted.

Its composition was firmly fixed at 100 during the time of the Roman kings’ ruling as the councils.

However, later around the 2nd Century, the Senate was expanded up to 300 during the time of Gaius Gracchi and Tiberius. But, it tripled to 900 under the rule of Sulla.

In like manner, Sulla, who planned to impose substantial land reforms, would triple this figure a century later when he expanded the Senate to 900 members.

Julius Caesar, on the other hand, recruited hundreds of members, and the Senates reached the count of 1000. But, Roman Emperor Agustus limited the enrollment to 600.

Despite proper legislation, the Senate did possess essential obligations making its view critical to the operation of the Roman government.

To begin with, senators debated internal and foreign affairs and oversaw necessary relations with international countries. They also handled Rome’s monastic life and, more significantly, the state’s finances.

The Consuls

Rather than a king, the new government-appointed consuls, two in total, to guard against authoritarianism.

These persons were chosen by the Comitia Centuriata, a national assembly, rather than elected by the populace.

As such, each consul conducted a one-year, non-consecutive term, though he might be re-elected for a second or third time.

Moreover, consuls enjoyed absolute executive power as political and military heads of state, leading the army, ruling over the Senate, and introducing laws.

Nevertheless, as a precaution, each consul had the option to veto the judgment of the other – an intercessio.

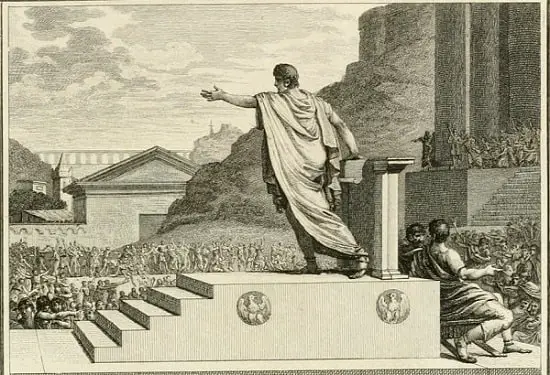

They wore a traditional woolen toga with a purple fringe as an emblem of their authority, sat on a unique chair or sella curulis, and were accompanied by at least six special aides of lictors. The fasces, a knot of rods and an ax, was their emblem.

At the end of their one-year tenure, the Emperor called them to account to the bicameral legislature for any judgments or acts taken.

Several consuls would have their responsibilities expanded by becoming proconsuls, governors of one of the numerous Roman provinces.

Traditionally, only patricians were eligible for the job of consul. Still, plebeians gained eligibility in 367 BCE, and by 342 BCE, the legislation mandated that one of the two consuls be a plebeian.

Julius Caesar, Marcus Licinius Crassus, Pompey the Great, and Mark Antony are notable consuls.

The Assemblies

Rather than the Senate, various leading assemblies were given the jurisdiction to implement the laws.

Initially, there were some legislative bodies during the reign of the Kings and also under the monarchy. They were called the Comitia Curiata (later changed to Comitia Centuriata) and the Concilium Plebis.

While these assemblies were not considered to be genuinely democratic, they did wield the people’s authority until the rise of the Roman Empire.

The initial Comitia Curiata, representing the three principal tribes after the fall of the Monarchy, forfeited the ability to write laws. But maintained lex curita de Imperio’s power which consisted of the authority to ratify the installation of magistrates.

Similarly, it also observed the induction of a will, priest, and adoption.

Ultimately, it became primarily ritualistic over time, and a new assembly based on wealth was established.

This newfound body’s membership was split into a group of 100 men for 373 participants.

During the voting process, the wealthier ones gained the majority, as the weaker or the poor ones were outvoted by the group of those chosen 100 men.

The meetings were mostly held in the Forum, but the Centuriata conducted their meetings at the Field of Mars, which was located in Campus Marcus’s city.

Its responsibilities included:

- Choosing several magistrates (consuls, praetors, and censors).

- Passing legislation.

- Declaring war and peace.

- Imposing the death sentence on Romans charged with political crimes.

The Magistrates

During the beginning of the Republic, the consuls discovered that they needed minor magistrates to supervise numerous administrative responsibilities.

Thus, a few of these offices had previously existed under the king. Many people would eventually use these lower-level appointments as a stepping stone to the consulship.

The cursus honorum was the name given to this “route.” The praetors were amongst these “lesser” magistrates.

They were the only ones outside the consuls to wield imperium power, with the jurisdiction to judge over the Senate and lead the army.

In addition to filling in for the consuls when they were absent, their formal role was to manage the Republic’s judicial tasks, including civic and regional jurisdiction.

And then there are the quaestors, who gained the power of quaestores aerarii or command of the treasury in the Forum of Rome. They were in charge of collecting both taxes and tributes.

Additionally, the aedile was also another significant figure.

Initially chosen to govern the temples, aedile responsibilities grew throughout the Republic’s early years (although this position disappeared with the onset of the Empire).

This official oversaw public records, administering public works (such as roads, water, and food supply), as well as marketplaces, celebrations, and games.

The Rule of Law and the Tribunes

The patricians held the proper authority in the Roman Republic, which could not last for long.

Plebians, who were involved in doing most of the work and also held a higher number of counts in the army, went against the ongoing authority and sought equality in the administration.

This struggle resulted in a class war that began in 494 and lasted until 287 BCE. It was termed the Conflict of Order.

The outcome of this conflict was the formation of the assembly for the plebeians, termed the Concilium Plebis, which was taken as a positive result.

The plebeians with this new formation may vote tribunes, who governed for a year like consuls. Their significant role was to protect plebeian rights from patrician oppression.

Likewise, their responsibilities were comparable to those of consuls, but they had the authority to veto decisions made by the magistrate that would affect the plebeians.

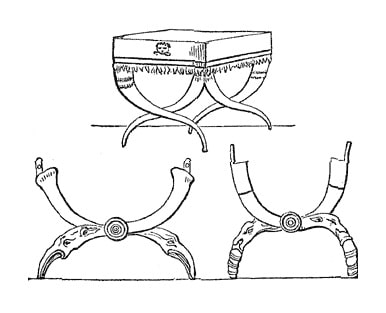

Likewise, to further preserve plebian rights, the law of the Twelve Tables was created that came out as the first written constitution in Ancient Rome and a major revolution in the Roman Laws.

Consequently, all citizens were given right to appeal against the magisterial judgment if that affected them in a wrong way around the 4th Century.

The Emperors

As Rome’s borders grew northward into Gaul, eastward into Asia, and south into Africa, the Republic’s governance could not keep up, ushering in the first emperor, Augustus, and establishing an empire.

Under the Emperor’s power, public assemblies all but vanished, and the Senate became increasingly ceremonial.

As a result, they would only truly support the Emperor’s wishes.

Augustus was granted supreme executive authority by the Senate and given powers beyond that of a consul or tribune – consular imperium and tribunicia potestates – including the potential to enact laws and veto laws and order the army.

The Magister Populi and the Censors

A censor, mostly the former consul was a job regarded as the peak of a person’s career.

Censors oversaw public morality, registered citizens, and the property they possessed, excluded someone from voting, and conducted the census.

Similarly, a work term for a censor was a total of 18 months, and he was chosen by voting in a time interval of around 4 to 5 years.

This stance was approved and favored by numerous ex-consuls as it served them with several unique benefits.

Aside from taking the census, he also may condemn or exclude someone from voting.

Conclusion

The Roman government of the old Empire had a sophisticated method of power partition that protected against tyranny by a single individual.

A voting public held the majority of power. While it was not flawless by any means, it did give some people a say in how their government ran.

There were elected leaders as well as a legislative body.

Considering the backdrop of ancient times and modern forms of administration and its albeit restricted representative features, Rome will remain an exceptional example of an effective ancient democracy.