During World War 1, the term “Doughboy” was influential among American infantrymen. Although the term’s origins are unknown, it was still used until the early 1940s.

Moreover, the 1942 song “Johnny Doughboy Found a Rose in Ireland” rocketed the term among troops. It was sung by Dennis Day, Kenny Baker, and Kay Kyser, among others.

Likewise, the 1942 theatrical picture- Johnny Doughboy, also comprises the term’s diaspora. The protagonist “Johnny Doughboy” in Military Comics is also another example.

During World War 2, however, it was eventually superseded by the term “G.I.”

The term “doughboy” likely emerged for the first time in records of the war of the Mexican–American between 1846 and1848. It was applied to the infantry of the United States Army, with no known precedent.

Several explanations have been proposed, however, to interpret this usage. One such theory comes from the cavalrymen.

They likely used the phrase to mock foot soldiers. The brass buttons on their uniforms resembled the flour dumplings or dough cakes.

It might also be because the soldiers polished their white belts with flour or pipeclay.

Another theory comes from observers who remarked that U.S. infantry units were continually covered with dust due to the elongated march in the dusty and dry Northern Mexican terrain.

This march made the marching men look similar to the mud bricks and the dry dough around the place commonly renowned as adobe. Hence, the term adobe was then converted into doughboy.

More still, another theory comes from soldiers’ technique of turning 1840s and 1850s field rations into doughy flour-and-rice mixtures cooked on the ashes of a campfire.

However, this does not clarify why only infantry soldiers were given the title.

One argument for the term’s use in World War 1 originates from female Salvation Army participants. They traveled to France to prepare millions of doughnuts. They then delivered them to troops on the front lines.

This theory has flaws, too, as it overlooks the term’s use in the previous war. Moreover, one joking approach to the term’s etymology originated during World War 1.

Much like the literal dough, Doughboys were “kneaded” in 1914 but did not rise until 1917.

How many U.S. soldiers died during World War 1?

Content

The United States suffered more than 320,000 casualties in World War 1, comprising over 53,000 killed in action and over 63,000 non-combat-related deaths.

How many African-American soldiers died in World War 1?

In World War 1, between 370,000 and 400,000 African Americans served the war efforts. Most enlisted were appointed as stevedores, camp laborers, and logistical support. About 40,000 to 50,000 fought in combat, and about 770 were killed.

World War 1 and Doughboys (U.S. Servicemen)

The Doughboys contributed to shifting the tide of the war because they were still to come in their millions before the war finished. They were arriving and managed to keep the western allies fighting in 1917.

Hopes of the Doughboys’ arrival helped them cling on until wins were gained in 1918 and the dust settled. These triumphs were achieved, of course, with the assistance of U.S. troops.

Many combatants and sympathizers from beyond Europe, such as Canadians and Anzac troops (Australia and New Zealand), also contributed heavily.

To begin with, when the First World War started in August 1914, none of the 48 sovereign states that comprised the United States of America (USA) favored siding with either opposing power.

They included The Entente Powers (Britain, France, and Russia) and the Central Powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan) (Germany and Austria-Hungary).

The United States possessed a proficient regular army of 100,000 soldiers, half of whom served overseas.

There was also a tiny National Guard (state-based militia) of approximately 30,000 people.

The United States had no foreign affiliations, and the President (Woodrow Wilson) rendered his country’s stance very clear when he issued his Declaration of Strict Neutrality on August 19, 1914.

The multicultural makeup of the population, with considerable numbers of Europeans from all combatant countries, made any other option politically unfeasible at the time.

Soon, however, the combatant nations’ requirements for food, armaments, and all types of tactically critical resources sparked a boom in the American economy’s industrial and agricultural sectors.

This resulted in a massive influx of cash and assets into American coffers. This boon also helped the eastern states of the United States in particular.

During the first five months of 1914, the Entente Powers – or the Allies as the world later called them after September 1914 – acquired approximately $1 billion in American commercial goods.

It had escalated to more than US$ 10 billion by the end of the conflict. For the current time, it was an astounding sum.

Thus, to pay for all of these items, prominent eastern financiers made massive multi-million dollar loans to the Allies at the same time.

Loans were made to the Central Powers early in the conflict, albeit considerably smaller.

The severe limitation of the Allied and Central Powers’ merchant marine fleets’ global activities also created unprecedented commercial opportunities.

Then, these gaps were quickly filled by American traders, particularly in South America and Canada.

At the same time, America was also making the most of the sun’s rays. The majority of its citizens saw no need to join what they perceived as European insanity.

America and the German Threat

Nonetheless, certain members of the wider populace and top military officers pressure President Wilson to raise the military service.

They urged him to engage the country more fully in foreign politics. This propensity was fueled by what was perceived as German viciousness and militant belligerence.

American citizens used the mistreatment of the Belgians as evidence, including the intervention in Mexico and Latin America.

Even covert actions of the Allies’ industrial assets in the United States were questioned.

All of these annoyances paled in comparison to the American public’s anger at the German Navy’s escalating use of unrestricted submarine warfare.

The disregard of Maritime regulations moved even the generally placid Western States of the United States to protest.

The egregious violation of the Rules of the Sealed to unrest.

In response to these complaints, President Wilson suggested a state of ‘Limited Preparedness’ in September 1915. Shortly after, Congress enacted the ‘National Defense Act.’

It authorized a modest expansion of the Regular Army to 140,000 soldiers. It also comprised a 400,000-man boost in the National Guard reserve.

All personnel was required to serve overseas in the future. The United States tentatively braced for war.

The Catalyst for War

The impetus that eventually led to the United States’ engagement in the war came, ironically, was the Presidential Elections of 1916.

After the ‘Sussex’ event, the German Navy suspended unlimited submarine warfare. It allowed Wilson to run for office on a ‘Keep us out of the war’ platform.

Wilson won the election by a slim margin on this basis. Despite his publicly stated goal of keeping out of the war, there were apparent indicators.

He and his aides were already moving toward active participation in the conflict.

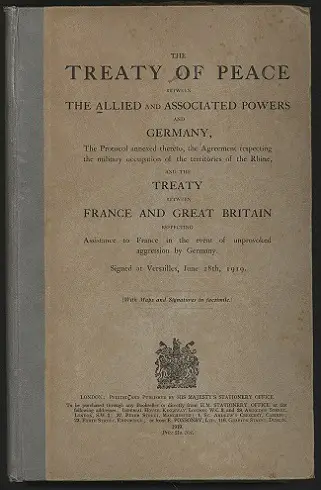

In this line, on December 18, 1916, the freshly re-elected president launched another round of diplomacy based on his ‘Peace Note’ to all combatant states.

It requested clarity of their war objectives to promote a cease-fire discussion through him. However, the Allies rejected the subsequent German ‘Peace Offer.’

This new treaty was nearly identical to the criteria set out in the very demanding German offer. On December 12, 1916, the latter was proposed a week before Wilson’s.

Declaration of War

President Wilson’s initial act in escalating the possibility of war was petitioning the U.S. Congress for cash to battle the U-boat threat.

Congress approved this request. Wilson then requested permission to enter the Allies’ side on April 2, 1917.

However, it was agreed that there would be no formal alliance with the Allies; instead, the United States would participate as ‘An Associated Power.’

On this premise, the German State declared war on April 6, 1917, followed by Austria-Hungary the next day.

The president put this onerous task upon the American naval forces and military leaders to induct and educate these conscripts for armed duty with little prior preparation.

The Great War similarly put the American economy in a war posture with centralized planning. This resulted in a massive increase in output, not only for American soldiers but also for the Allies.

The highly successful shipbuilding effort was critical in getting men and supplies out across the Atlantic to the Western Front in Europe.

The United States deployed soldiers overseas to shield foreign soil for the first time during the Great War.

And herein lies the problem of the term Doughboys and the debate of what should the foreigners call the Americans?

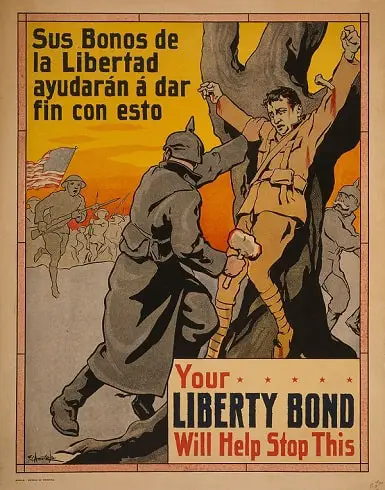

“Yanks,” “Sammies,” and “Pershing’s Crusaders” were just a few of the nicknames given to America’s military troops during World War 1.

Pershing’s Crusaders and Sammies (for Uncle Sam’s troops) also appeared in advertising and propaganda posters. And somewhere along this grapevine, the term Doughboy bloomed into existence.

Infantry Conditions in the Great War — Food and Filth

In the trenches, it was hard to keep clean. Diseases bred by dirt. With just the most primitive treatments available, many now benign conditions were fatal then.

They also depleted the fighting strength of the Doughboys. Sickness almost accounted for 71% of duty-time lost in the AEF in France.

Battle injuries, on the other hand, accounted for only 22%. In 1918, influenza, pneumonia, and other respiratory infections accounted for 17.33% of all AEF hospital admissions.

82% of those admitted suffered illness-related deaths. The Doughboys also suffered from cooties because of the filthy conditions in the trenches.

The minor cootie bugs gorged themselves on the blood of their victims. These vermin were roughly the size and color of tiny grains of uncooked rice.

A black cross could easily be seen on the bug’s skin when fed on human blood. This indicated that the bug’s digestive tract was in the shape of a cross.

Doughboys and the troops saw this as a “black German Iron Cross.”

Subsequently, the Army had a ‘delousing’ program that included visits from a sizeable tank-truck-like device and a steam generator. But they were infrequent at best.

At worst, the service members had to strip down entirely, hurl their clothes into a bundle, and then flung into the tank.

The live steam cooked the bugs. However, the troops would generally freeze during this time. The gadget also never appeared on a nice warm day, but only during winter.

Doughboys were louse-free after submitting to this until they got back into the hay bedding and became afflicted again.

Food, or rather its low quality, was another constant on the Doughboy’s thoughts.

There never seemed to be enough food for most people during the war. All too often, the troops were served a variation on what they affectionately referred to as ‘slum’ or ‘goldfish.’

Slums were basic stews with limitless variations but no appeal. Goldfish was canned salmon. Another staple was ‘monkey meat,’ a strange-tasting French tinned beef from Madagascar.

The ration also consisted of tomato juice, which may have been nutritious and thirst-quenching. Officially, U.S. soldiers at that time were permitted to purchase ‘light wines’ and beer.

However, other fortifying beverages, such as champagne, whisky, and brandy, were prohibited. Any establishment where such spirits were sold was also off-limits.

Conclusion

It’s worth noting that ‘doughboy’ was originally a nickname for an inanimate thing. It was a type of flour-based dumpling that evolved into the doughnut.

It was famous by the latter half of the eighteenth century. This circumstance could be where the soldier’s doughboy name originated. It was passed down to soldiers to first look down on them.

No matter what moniker they were given, few could deny that the United States significantly impacted the conflict just by entering the war.

The massive effort required to deploy and equip two million service members in less than a year was nothing shy of inspirational.

In World War 1, the modern American Army was founded due to this critical historical event.

From April 6, 1917, to November 11, 1918, approximately four million soldiers served in the United States Armed Forces during the war.