Alfred North Whitehead has quipped that the general characterization of European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.

In a way, he has surmised that the philosophical drafts that followed after Plato is a tiny fraction, analogous to a footnote, in comparison to his works. He speculated that his endeavour in philosophy is a cavern of inexhaustible suggestions and I cannot agree more.

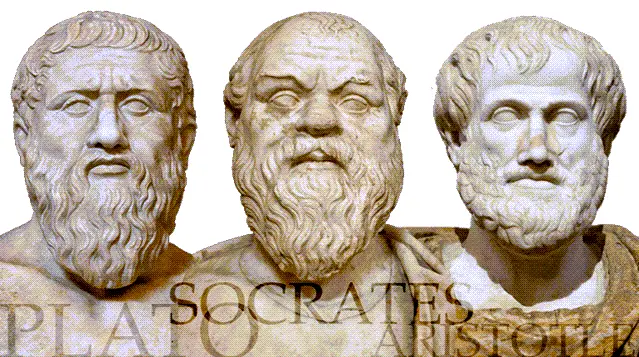

Plato (c. 428 B.C.- c. 347 B.C) was an Athenian philosopher, a disciple of Socrates, and a teacher to Aristotle. He was the founder of Academy, the institution for people pursuing higher studies, and Platonism, a new branch of philosophy.

Born into an aristocratic family, Plato always wanted to join politics. Somehow, he was introduced to Socrates and soon became a disciple. His works include Apology, a purportedly imaginative and satirical version of his defense trial. Others include the Republic and the Statesman and the Laws, which are the cornerstones of political philosophy.

In this article, I am counting down the top ten contributions of Plato.

10. Mentor of Mathematics

Content

Republic, written in around 375 B.C., demonstrates via conversations the value Plato ascribed to mathematics, particularly five subjects such as arithmetic, plane geometry, solid geometry, astronomy, and harmonics.

Here he argued that learning arithmetic broadens our mind and swerves it towards the truth. It compels us to perceive the equal and opposites and unity and plurality in terms of numbers that stimulates us to transcend beyond this transient world to merge with absolute unity.

The number one is also one and infinite in multitude and so are all numbers. He posited the correlation of mathematics and philosophy as both operate better with reason and logic, concerning the tangible and the intangible forces.

Further, he emphatically urged teaching mathematics to the military, the guardians of their city, for its practical applications. A general with the knowledge of geometry knows his stance, their position in a war or any other strategic military manoeuvre and turns it into their favour.

Then he launched to assign the importance of astronomy. The changes of seasons, rotation and revolution of the planets are equally crucial to a commoner as it is to the farmers and the sailors. Similarly, mathematics and logic apprehend every degree the planets tilt and their speed.

Deducing, Plato encouraged the study of numbers as they trained every faculty of the mind and were characteristic of elusive and intangible as was philosophy. They complimented each other, and when studied accordingly, they reveal the mysteries of the earth and the heavens.

9. Platonic Love

Out of other categories of love such as physical, emotional and the like, comes a new terminology called Platonic love. It is characteristic of omitting sex from the relationship where the partners enjoy close connection without physical consummation.

While Plato did not coin the term, he was the first in Western literature to describe and analyze love in any great detail. Eros was the word from which we derive the word erotic, which has a heavy overtone of passion along with it.

Plato, in his ancient treatise, Symposium, concerned with love and its dissection by at least six wise men. The setting where the dialectics take place is a dinner party, where everyone shares their account of this universal principle of love that undergirds all human activities.

His thoughts regarding the subject were reported by Socrates, who himself claims to be quoting a priestess called Diotima. All in all, the author illustrated the dichotomy of the object of love and nature of love.

He furthers his argument by stating that love is not the desire to possess, which is the pre-supposed idea of ancient Greece, but rather the quality of appreciation. Finally, claiming love to be more or less lacking rather than coveting.

Plato uses dialectical methods among the speakers to shed astounding insights into the whole spectrum of love. Most scholars interpret it as encomia rather than analysis.

Platonic doctrine incorporates the idea of agape, the pinnacle of love and purity. It extended to the Christian love of God by man and vice versa. In a way, Platonic love is a summation of agape.

8. Plato and Education

For Plato, education was of paramount importance, wherein laid the foundation of a stable and prosperous state. He truly believed that an educated society needed no laws, while nothing could suffice an uneducated one.

The categorization of education levels and optimum age echo the core tenets of his proposed style and reformations in the ancient Greek. The system of mandatory education to both male and female reflects his original theories.

As advanced in Book VII of the Republic, the objective of Platonic schooling was to make their pupils able to see the light of their soul. He proposed it to be the objective of education itself: to enlighten people of their inner soul by inducing the right environment.

Platonic education was, therefore, devoid of any step-by-step rule to instil in the minds of the learners. It emphasized on the mere recollection of all knowledge that the soul inherited from the past life.

The Meno deals with this theory of reminiscence. Hence, it stemmed the role of teachers, to help guide the students tap into that latent reserve of knowledge.

He contends that education should not be limited to a certain age and should be pursued generously throughout our life. While it is an evolving agency, our soul is a malleable entity. Thus, they are perceived differently at different stages of life like infancy, adolescence, youth and adulthood.

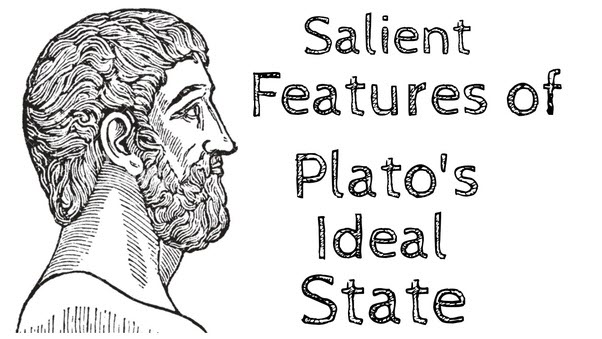

7. Ideal State

In his book, Republic, Plato has tried to paint a picture of an ideal state, which is more or less utopian. According to him, the citizens can be at their best only in that state.

He starts with human beings and divides the soul into three elements: reason, spirit, and appetite. According to him, appetite gives birth to love, reason guides action and unity, and spirit inspires the people for battle, ambition, and competition.

He, however, attached great importance to reason alone. In his ideal state, there shall be functional specialization. There shall also be overproduction to raise national wealth. The warrior shall defend the frontiers and the philosophers will rule the nation.

An ideal state must be governed by a philosopher-king who should be a seeker of truth and wisdom. He should possess high qualities of head and heart.

There should be equal treatment of men and women, who should attend compulsory education. The state should have full and final control over education.

For him, it was the only agency which could produce philosopher-kings and train the minds and thoughts of the people in the right and proper direction. It should promote social welfare, while personally, it should bring the soul closer to reality.

He believed that justice was an essential and integral part of the state to keep its organs and individuals in close harmony with each other.

It was more about functional specialization where everyone was required to remain within their limits. Under it, there was perfect harmony among various sections of the society; none was to infringe the rights of others.

Although it entails numerous criticisms, these faculties still reverberate in a democratic state of modern times.

6. The Propounder of Political Philosophy

The Republic is considered a philosophical omnibus that deals with not just politics but all aspects of human life including education, ideal man and society, morality and ethics.

The central tenets of political theory or political philosophy are state, justice, rights, and liberty, all of which were penned by Plato in his book.

Ancient Greece had polis or city-states, which were always conflicting. It was Plato who extensively studied broader phenomena of legitimacy, rights, duties and also the grouping of both the ruler and the subject.

He dissociated the presumed way of living life, which was through glory and chivalry, and replaced it with arete (moral virtue). He also contended against the democratic regime of the then Athens, claiming that it was a mob mentality.

He dismissed democracy as a chaotic spectacle of ideas, opinions and interests pitting against each other, without settling on common ground. They all were swayed by demagoguery in the end.

In the Republic, he presented a new model of educating citizens and how to organize political institutions for the welfare of the state.

5. Theory of Forms

Plato translated his theory of existence (ontology) and theory of knowledge (epistemology) in many books, particularly in the Republic. It deals with the existence of certain things in the world and the process of grasping it.

He addressed these precepts using a metaphorical story, which is one of the most popular and the most cited one. Through his works, he had attempted to dissect concepts of beauty, ideals and justice.

He cited that imagining the perfect or ideal form of anything was a matter to be contemplated on. That allowed us to visualize the flaws or gaps in the perfecting of an object and prompted us to fill it.

He opined that perfectionism in any given thought or object was found in its ideal form, created by the master or a guide. It is in finding that Form that we can arrive at our goals. It may sound a little strange but for Plato, philosophy was the instrument that could help us find them.

In other words, it is a conceptual notion that produces other objects like tributaries. In the Platonic scheme, every matter is merely a defective copy of its ideal Form. He contends that all that is visible to the naked eye are subordinate to the higher, invisible vortex.

He suggested that reasoning, studying philosophy and logic (logos) enable us to fathom the eternal and the constant. Our senses only allow sight, smell and appearance of the transient and imperfect copies of it.

4. Theory of Knowledge or Epistemology

The learned man adheres to the truth and doesn’t change with the changing world. He believed that at the core of the elusive material world lied the Reality, which was hard to grasp by a common passerby.

In books VI and VII, he opined that only the philosophers should rule as only they could distill pure elixir of knowledge from the complex world of mere opinions and beliefs. He stated that the former was epistemic and the latter was derived from the Greek word, Doxa.

As an ardent critic of democracy, he wanted philosophers to rise above petty clashes of personal interests of the mass and apply their objectivity in politics. He believed that epistemology and ethics were powerful twins in the administration of justice.

Like his master Socrates, he also believed that the soul is the all-knowing and all-pervading entity. The soul knows no limitations in terms of the acquisition of knowledge. However, it is shrouded with material identifications that obscure our vision.

According to Plato, there are forms of objective truths that cannot be perceived with our senses. And those that are easily availed with the help of these organs aren’t absolute but flawed reality. This phenomenon is better illustrated in his metaphor of the sun, the dividing line, an allegory of the cave.

In conclusion, when the history of epistemology is looked up, we find the bold letter of Plato as the progenitor. In the years that followed, many scholars and intellectuals have further expanded on his concept.

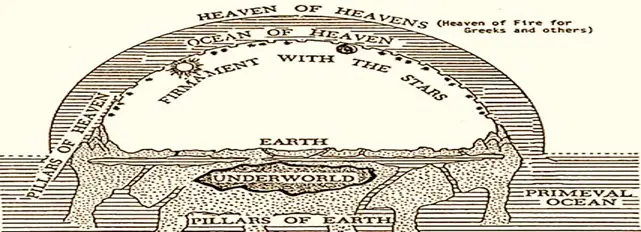

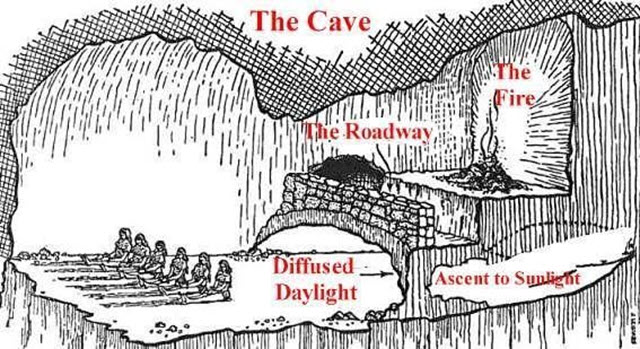

3. Allegory of the Cave

Allegory of the Cave is most probably the most famous single passage in the history of western philosophy.

In a dialogue in the Republic, Socrates begins describing a strange image to Glaucon, his interlocutor. There were cave dwellers, bound up in chains such that they cannot turn their head around. And they are looking at shadows cast on the wall.

Those shadows reflected from a low wall in a short distance with fire where people were holding things up. They were also making sounds that echoed in the base of the cave. So the people at the bottom were seeing shadow images and mimicked sounds coming along with them.

Then there was a real exit to the cave up above, where the truth lied. When Glaucon exclaimed the strangeness of the image, Socrates replied that these prisoners were us-only looking at the shadow-images.

The prisoners were naming the objects they perceived and identified with them. But the real problem is that what we are seeing is not real, it’s only a copy of a copy of a copy (Fight Club, anyone?)

In essence, many times removed from really identifying the things, as they descend from the real exit of the cave to the statue form in the middle and finally projected to the prisoners.

In the end, one of them gets released compelled to stand up. He turns around applying all effort and sees the statues, a step closer to seeing objects nearer to reality.

Moreover, when he reluctantly drags up a steep and rugged ascent, the dazzling light beyond the pits of the cave temporarily disorients him.

Gradually, he adjusts to it and fathoms Reality-the blinding sun and not its mere reflections. The Sun is the first principle of everything else, which when apprehended, he becomes wise.

2. Consolidated the Teachings of Socrates

Plato instantly became a disciple of Socrates. He witnessed the trial and execution of his master that left an indelible mark on him.

Apology is a book that chronicles the events that occurred between the trial and execution. Plato has satirically recounted the last few meaningful words uttered by Socrates.

Besides that, Plato has authored at least 24 books, all of which mostly depict Socrates conversing with various other characters. His dialogues are in the form of a dialectic, deductive and ingenious thoughts.

It is through the amalgamation of his dialogues and their interpretations that has moulded the framework of Western Philosophy.

Plato writes in such a manner that he and Socrates become almost the same person. One might not know if through Socrates, Plato lays down his philosophies or they’re originally the teachings of Socrates. It is a fundamental problem in philosophy which scholars regard as the Socratic Problem.

Regardless, Plato heralds as the preserver of this potent specimen and his teachings. Almost all philosophies propounded from the books of Plato are merely the words of his master.

More than expounding on them, Plato has sincerely paid homage to Socrates through his works.

1. Academy of Plato

The term Academy marks an area outside the walls of the ancient city of Athens, where one of the three large gymnasiums were founded and operated.

It was a verdant park with big platanes and bore small sanctuaries of Apollo, Athena, and Prometheus. It was the setting of the Academy of Plato, a worldwide iconic institution, established in c. 387 BC.

Historically, it was not much of a formal educating mechanism in the real sense of the word. Furthermore, only the elitist availed enrollment within its premise, despite it being open to the mass.

Insofar as the charges were concerned, there were none until Plato’s time. Similarly, the fine line between a teacher and a student was blurred.

There was no trace of the conventional active teacher and passive student environment, where the former indoctrinated the latter. Plato posited his pupils with problems to be resolved by them. The institution boasted a good many graduates and politicians of the future.

The life of the institution has faced three periods: the old, the middle and the new. The ancient period was run by Plato and most probably his student Aristotle, while the later periods by his successors.

Deducing, it laid the foundation for an institution for higher education, the significant trajectory of which has covered all centuries.

Conclusion

The ideas and concepts of the past get replaced every day. A new theory enters, thereby rejecting its predecessor.

But there are also those timeless gems that remain relevant in all ages. Plato’s philosophy is one such example.

Not only are his ideas treasured, but they are also, evidently, the portals through which novel philosophical schools emerge. Thus, Plato was such a character from history who was far ahead of his time.