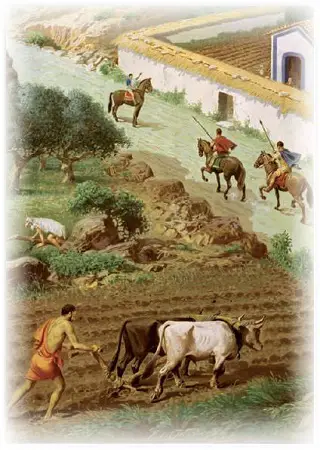

Romans exemplified farming techniques 1000 years. The initial Roman Republic (from 509 to 27 BCE) and the subsequent Roman Empire ( from 27 to 476 CE) grew from modest origins.

However, Rome ruled most parts of the Middle East, Europe, and Northern Africa. It encompassed the Mediterranean climate, one of the most prevalent agricultural environments.

The biosphere of the Mediterranean was signified by parched, hot summers and cold winters.

In other words, the Roman empire encompassed significant geographical variations ranging from the deserts of Africa to the freezing mists of northern Britain.

As such, temperature and rainfall varied considerably between the north and south of Italy. Similarly, geology and scenery also changed dramatically from the Alps to Sicily.

It would thus be unrealistic to expect any unified agricultural system to have existed in Italy, let alone the remainder of the empire.

Nevertheless, A trio of crops was most pertinent in the Mediterranean region: grapes, cereals, and olives.

Not to mention agriculture employed most of the population controlled by Rome.

Initially, the agriculturally involved population were tiny land owners that managed to harvest on a small scale, which expanded into owners owning large lands, known as latifundium.

The affluent held enormous estates and were labored primarily by slaves.

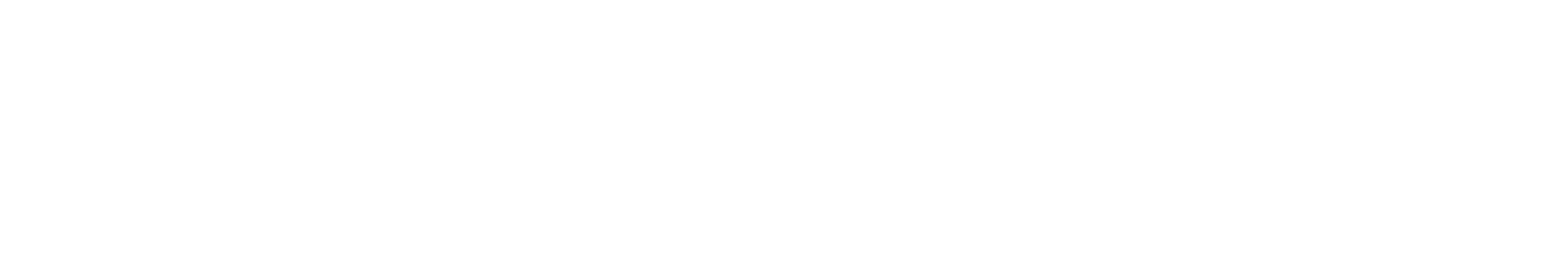

The expansion of the population living in urban areas, particularly in Rome, also necessitated the creation of commercialized markets.

The agricultural products, majorly grain, began being traded long-distance to fulfill the demands of people living in cities.

What contributed to Rome’s thriving agriculture?

Content

The mild climate of the Mediterranean enabled Romans to cultivate wheat, grapes, and olives. The climate also made year-long agriculture possible.

Rome also had the advantage of being near water, with the Tiber River draining the agricultural lands and helping it prosper.

How did the Romans feed their growing populace?

Among the chief logistical concerns for Romans was adequately feeding its military, men, cavalry horses, and pack animals, usually mules.

Indeed, wheat and barley grains were the primary food sources of the time. Animal meat, olive oil, wine, and vinegar were also abundant. Another principal food source was legumes.

Did the Romans eat rice?

The ancient Roman diet knew of rice, but it was rarely available. Instead, the Roman diet consisted of grains like barley and legumes that were abundantly grown in groves.

Besides, there were also very few citrus fruits, but Romans did enjoy figs, grapes, and oranges.

Agricultural Crops of Ancient Rome

Olives

The Romans cultivated olive trees in poor, rocky soils, frequently in areas with little precipitation.

Olives and the fruit’s oil were not only an integral part of the ancient Mediterranean diet but also one of antiquity’s most prosperous enterprises.

Olive cultivation grew with the Phoenician and Greek colonization. They ranged from Asia Minor to Iberia and North Africa.

Excellent olive oil became a valuable commercial item. They were popular through the Roman period and beyond. Moreover, the olive subsequently developed to have broader cultural importance.

Most notably, it was a symbol of peace. Olives were also the victor’s crown in the ancient Olympic Games.

The olive tree was susceptible to freezing temperatures and was intolerant of northern Europe’s colder weather.

Likewise, it did not do well in high, cooler elevations either. Thus, the olive was primarily farmed along the Mediterranean Sea.

In the ordinary Roman diet, olive oil provided around 12% of the calories and almost 80% of the required fats.

The Romans also pushed olive production to more marginal areas, such as central Tunisia and western Libya.

They did so from the first to third centuries CE, which required massive irrigation systems to make farming feasible.

Moreover, the Romans’ reliance on olive oil is also exemplified by Septimius Severus’ decision to collect it as part of provincial taxes. He then redistributed it to the inhabitants of Rome.

As the Roman Empire grew, so did the demand for olive oil. Constantinople was one of the most important importers.

Indeed, farmers created massive numbers of olive farms (and vineyards) across Syria and Cilicia to supply the demand.

This is also credited with causing a regional economic boom in the third and fifth centuries CE.

Legumes

A tiny grain of wheat could grow a plant with ten or twenty grains on its head under the correct conditions was a simple marvel for ancient Romans.

The repetition of this farming process allowed millions across the Mediterranean to eat bread.

Nevertheless, it was a complicated operation that necessitated regular bouts of heavy labor.

It also required a solid understanding of technique, a modest armory of instruments, and various sorts of seed.

Farmers picked which legumes to grow yearly based on a general goal of self-sufficiency.

This led them to value productivity and robustness in the face of climatic extremes over other factors like flavor.

Numerous references to threshing suggest that Greek and Roman farmers produced legumes on a considerable scale.

Chickpeas, lentils, peas, and broad beans were as significant in ancient Mediterranean cuisine as today. Roasted chickpeas were a favorite snack, while the others were used to make soup.

Legumes were also thought to be drought-tolerant. Moreover, they could also be cultivated in the summer.

However, wide beans demanded a lot of water and could not be grown in regions like Attica without irrigation.

The ancients also grew cowpeas, vetch, and lupines as animal feed and famine food for men.

Grains

The ancient Mediterranean’s principal cereals were barley and wheat. Much like legumes, farmers picked which grains to grow yearly based on a general goal of self-sufficiency.

Long-term, however, desire for superior tasting and textured breadstuffs prompted a gradual change from the barley regime of early Greece to the bread wheat culture of Imperial Rome.

Similarly, barley has two cultivars that were routinely grown. One was a two-row version that was richer in carbohydrates but lower in protein.

The other was a six-row form that was higher in protein but lower in carbohydrates.

Barley also had the largest grain yield per plant in semiarid terrains.

It was the main grain for farmers in Attica, where people consumed it in barley cakes and porridge.

However, barley was viewed as a second-class grain by the Romans.

Roman Philosopher Pliny also indicates that farmers farmed barley primarily for animal feed. Josephus also claimed that the rich ate wheat in his day, and the poor ate barley in Palestine.

Likewise, emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum) was also one of the first domesticated crops and the main wheat of Classical farmers. Emmer grew well in Italy and the wetter regions of Greece.

However, it was hulled wheat, which meant that its individual grains, which are securely linked to their husks, must be dehydrated and crushed before processing.

Though it was never completely phased out, it did suffer increased competition from two types of naked wheat. The ears of wheat are named because their husks are more loosely attached to the grain.

The first competitor, the durum wheat (T. durum), was called semidalis by the Greeks. It was a Semitic name indicating its roots in the Near East.

Durum was ingested in several ways and is still used today for couscous and pasta.

However, it could not be milled into decent flour. On the other hand, the ancients used bread wheat, whose softer, moister grain gave fine flour for baking.

Durum was also grown throughout the Mediterranean, but bread wheat thrived in northern locations. These included the area around Pontus, which was the primary source of bread wheat throughout the Roman period.

Vines, Grapes, and Tree Crops

The Greek colonists introduced viticulture, or the cultivation of grapevines, to numerous cities, including Sicily and Southern Italy. Likewise, the Romans also received knowledge regarding viticulture from the Northern African Phoenicians.

Roman Empire, by 160 BC, produced an enormous amount of grapes using slaves, making grape wine one of the most drank wines around the Roman Empire.

The Romans even attempted to ban grape cultivation outside Italy from safeguarding their wine business.

However, during the 1st Century CE, some places, like Gaul and Spain, exported wine to Italy.

At every scale, vines and fruit trees were common in the ancient landscape. Figs and grapes were also native to Greece and well adapted to its soil and temperature.

But it was human ingenuity that made them plentiful and prolific. Farmers avoided producing new plants from seed since the resulting trees took a long time to mature. Most also did not grow true to type.

The most usual farming option was and still is to take cuttings from trees with desirable characteristics.

Farmers then planted the cuttings in a nursery and then transplanted the cuttings to a permanent home once their roots had formed.

Ancient farmers also grew olives from cuttings by grafting cultivated stock onto wild trees.

They then grew out knot-like trunk growths, termed ovoli.

New grape vines were also grown in Greece from cuttings. They were suckers transplanted into the soil and layered (pushing branches into the soil until they took root).

Subsequently, Roman farmers added grafting to their farming process.

Moreover, trees were meticulously pruned once they were mature enough to give fruit to ensure optimal productivity.

Pruning was, and still is, an art that needed a thorough understanding of how trees responded to varied cuts made at different locations and periods.

It required mastering and made the vinedresser a highly respected agricultural specialist.

Vegetables and Herbs

Kitchen gardens were not explicitly reported in Greece until the Classical era. But they must have existed in some form millennia earlier.

Vegetable gardening was both resource and labor-intensive. Even a small plot involved deep digging, artificial watering, annual manuring, and weeding regularly.

Gardening, on the other hand, was profitable if an urban market was nearby. Cato even ranked it as the second most profitable use of a given amount of land.

High profits also helped explain some technological developments reported throughout the Roman era.

Examples include waterwheels and valve pumps used to supply irrigation.

Other additional developments included attempts to lengthen the growing season for plants by using cold frames constructed of glass (ancient greenhouses).

The gardener’s handbook appeared as a unique literary genre for the first time in early Imperial Rome.

Gardeners could make a good living cultivating vegetables and herbs. But they could also make a good living growing flowers like roses and lilies for urban markets.

Flax and hemp were the two most significant fiber crops too.

Likewise, apart from legumes, the most significant vegetables in Rome were root crops (turnips, carrots, and radishes), and alliums (onions, garlic, and leeks).

Other vegetables comprised lettuces, beets (for their greens), celery, and the fruit of various ground vines (gourds, cucumbers, watermelons).

In like manner, herbs were less difficult to grow and manage than vegetables.

Yet they supplied seasonings that played a significant role in defining the character of an ethnic dish.

Culinary herbs used by the ancient Romans included basil, coriander, cumin, mustard, and mint.

They also used fennel, thyme, sage, parsley, oregano, marjoram, and saffron.

Bay leaves, and myrtle berries were also regularly used to enhance the flavor.

Moreover, the Romans also received most of their herbs from the Greeks, although they were the first to produce lovage (a celery-like plant native to sub-Alpine Liguria).

The Romans used lovage and other bitter herbs’ rue to a large culinary extent.

Animals

Domesticated animals served various, and sometimes contradictory functions, for ancient farmers.

From one perspective, they were coworkers, providing labor or other benefits (for example, manure) to the homestead.

They may, however, be viewed as products, like crops, to be milked, shorn of their wool, killed for meat, or sold off as needed.

Finally, animals were also fellow-creatures with needs for food, shelter, and water that had to be supplied, even if it meant competing with humans.

Thus, a farmer’s decision to grow animals, and if so, how many and what kind, was consequently influenced by various factors.

People traditionally appreciated animals for practical, religious, and sentimental reasons.

However, as Varro and Columella point out, agriculture, in the true meaning of the term, was concerned exclusively with planting and soil improvement, not with animals.

The extent to which animal husbandry and arable farming competed or complemented one other in the Mediterranean has been the subject of intensive scholarly investigation over the last few decades.

Likewise, horses were expensive to raise too because of their extensive training regimen and the vast quantities of high-quality feed they required.

Farmers fed horses barley, oats, melilotus, hay, and fresh grass. Cattle also required approximately 12 kg (26.5 lb) of grass, hay, legumes, or clover per day.

They also preferred well-watered grazelands but could also survive in dry grassland or woods.

According to Roman agronomists, farmers should have fed them on tree leaves during the lean summer months.

This diet would have kept the animals alive but rendered them sluggish and incapable of performing any labor.

Furthermore, animal farmers also fed cattle salt supplements at the end of the summer to make them gain weight.

In like fashion, pigs typically foraged in woodlands too, where they could root for acorns, grubs, and other aromatic trash.

On the homestead, farmers fattened pigs for slaughter on beans, barley, and damaged fruit. Similarly, sheep and goats, the ovicaprids, were less demanding than equids.

Cattle have always been far more common in the Mediterranean. Skins, milk, and meat were all produced by both species.

Not to forget, sheep also produced wool. On a more literary side, Arcadia, known as “the mother of flocks,” was later recognized as pastoral poetry’s spiritual cradle.

According to Cato, a 160-acre olive grove should have a flock of 100 sheep to manure the soil and reduce weeds.

Fodder and Other Crops

Columella mentions turnips as an important, high-yielding food crop.

Particularly in Gaul, they were utilized as winter feed for cattle. He also mentions Medic clover, vetch, barley, cytisus, oats, chickpeas, and fenugreek as “fodder crops.”

He claims Medic clover improved soil, fattened lean calves, and was a high-yielding fodder crop.

Likewise, Cato, the Elder, also recommended gathering leaves from poplar, elm, and oak trees in the fall before they dried fully and storing them for use as fodder.

After the wet season, turnips, lupines, and forage crops were planted.

Artichokes, mustard, coriander, rocket, chives, and leeks were also common agro crops in Rome. Other vegetables included celery, basil, parsnip, mint, rue, thyme, and beets.

Roman farmers also grew poppy, dills, asparagus, radish, cucumber, and gourd.

The Mediterranean climate was also suitable for cultivating fennels, capers, onions, saffron, parsley, marjoram, cabbage, lettuce, cumin, garlic, and apricots.

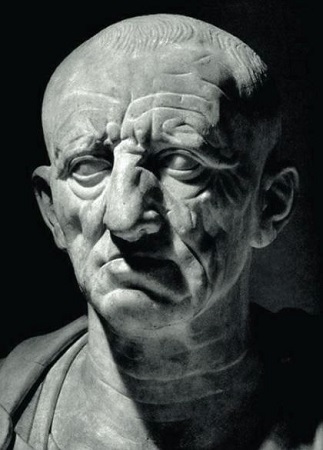

Farming Tools in Ancient Rome

Ancient Roman farmers used tools similar to the Neolithic period, like plows, sickles, rakes, shovels, and turf cutters.

The basic plow, or ard, was a frame with a sharp rod penetrating the soil to create a seed furrow.

It was employed in lighter, drier soils. On the other hand, the heavy plow, which featured a metal cutter blade, was utilized in clay and wet soils in northern areas.

Farmers also used iron shovels of various sizes in Roman farms to assist in readying the soil before growing vines and other fruit trees.

Farmers also used shovels to transport wheat from fields to wooden buckets and baskets.

During the Roman period, iron hoes were frequently manufactured triangularly and were also significant farming implements.

Likewise, a turf cutter, like a little and sturdier spade, had a hardwood shaft and a robust iron head.

Although turf cutters were mostly utilized to establish new roadways and fortify the empire’s fortifications, farmers also used them to break up hard, rocky soils for cultivation.

Similarly, rakes had iron prongs attached to a sturdy hardwood frame, commonly made of oak.

They were used to soften the soil before sowing and harvesting hay and grass for animal feed. The sickle was also an ancient Roman farm tool that farmers originally fashioned of wood and animal jawbones.

Sickles was made of iron and had long or short wooden handles throughout the Roman Empire. Slaves and farmers used them to harvest barley, wheat harvests, and grass for animal feed.

Fruit plants, such as fig trees and vines, were also pruned with small sickles.

The Perception of Agriculture in Ancient Rome

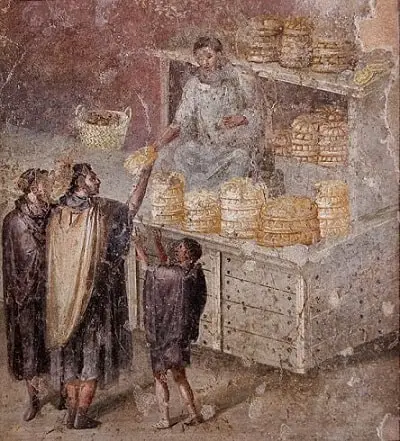

Agriculture was not only a fundamental requirement in ancient Rome but also revered as a way of life amongst some of the social elites.

Cicero also thought farming was the greatest of all Roman jobs.

In his essay On Duties, he said that “among all the vocations by which gain is acquired, none is finer than agriculture, none more profitable, none more joyful, none more fitting to a free man.”

Moreover, when people mocked one of his clients in court for favoring a rural life, Cicero defended it as “the teacher of economy, industry, and justice” (parsimonia, diligentia, iustitia).

Furthermore, farming manuals were written by Cato, Columella, Varro, and Palladius.

Additionally, Cato also claimed in his 2nd century BC work De Agricultura (“On Farming”) that the best farms had a vineyard, an arable garden, willow grove, olive arboretum, meadow, grain field, forest trees, vineyard cultivated on the canopy, as well as acorn bushlands.

Though Rome depended on resources obtained via conquest and conflict from its many provinces, rich Romans used the soil in Italy to grow various crops.

Besides, the citizens of Rome had formed a massive market for purchasing crops grown on Italian farms.

Not to mention, agriculture is possibly the most difficult component of the Roman economy to comprehend.

A substantial body of literature on Roman agriculture has survived from various authors who wrote during the second and fourth centuries BC.

Pliny the Elder’s Natural History also offers a wealth of agricultural information.

Inscriptions on stone are the second type of written evidence with the advantage of being original documents.

Due to their nature, they have not been tainted by the generations of copyists who have preserved literary works. Likewise, many ancient manuscripts written on papyrus have also survived in Egypt.

The manuscripts include price lists, customs charges (Diocletian’s Edict), boundary markers, and maps of land divisions.

Moreover, information on legal arrangements for the repair of wasteland is also available from these sources.

Farming Conditions & Percentage of People engaged in Agriculture in Ancient Rome

According to some estimates, four out of every eight individuals in the ancient Mediterranean were “country people” (agroikoi or rustici).

They worked as peasant farmers, herdsmen, agricultural slaves, or in some other capacity cultivating animals and plants.

The farmer’s life was a touchstone experience that epic poets regularly drew on as a source of analogies for heroic actions in battle. Here is an excerpt from Homer’s Illiad (17.53–60)-

“And just as a man will raise a healthy olive cutting in an undisturbed location where enough water runs to keep it moist—it is fine-looking when in bloom, as gusts from every wind shake it.

The white blossoms burst open until suddenly one wind comes in a massive blast and uproots it from its hole, laying it out on the ground—in the same way Menelaus Atreus’ son killed then stripped the armor from Panthos’ son, Euphorbus, of the fine ash spear.”

Romans formed most cities’ religious calendars around the local farmer’s calendar. The ostensible goal of ritual practice also guaranteed that harvests were plentiful and animals were fruitful.

Conversely, anxiety about crop success or failure led to well-known mythology, such as the story of Demeter and her daughter, Persephone.

Moreover, most things bought, exported, and sold throughout the Mediterranean are agricultural products.

The skilled urban inhabitants of the Classical world survived on the work of generally illiterate peasants, much like our world today.

Furthermore, farms in Rome were tiny and family-owned around the fifth century BC. On the other hand, the Greeks of this era had begun to use crop rotation and possessed huge estates.

In the third and second centuries, contact between Rome and Carthage, Greece, and the Hellenistic East strengthened Rome’s agricultural skills.

As such, during the late Republic and early Empire, Roman agriculture peaked in terms of productivity and efficiency.

Farming Practices and Organization of Agriculture

Speaking on a more general term, however, farm sizes in Rome were classified into three types.

Small farms ranged in size from 18 to 108 iugera. (One iugerum was roughly 0.65 acres or a quarter of a hectare.)

Medium-sized farms ranged in size from 80 to 500 iugera. Similarly, large estates (latifundia) cost more than 500 iugera.

The Romans also had four farm management systems. First was direct work by the owner and his family.

The second was tenant farming or sharecropping, in which the owner and tenant divide a farm’s produce.

Third was forced labor by slaves owned by aristocrats and supervised by slave managers. Finally, other arrangements included a farm being leased to a tenant.

To boot, the number of latifundia grew in the late Republican era. The land was purchased by wealthy Romans from peasant farmers who could not make a life.

Beginning in 200 BC, the Punic Wars also forced farmers to battle for extended periods. Some experts now argue that large-scale farming did not dominate Italian agriculture until the 1st century BC.

Similarly, cows gave milk on animal farms, while oxen and mules worked hard to tilling the soil. Sheep and goats also produced cheese and were esteemed for their hides.

Horses were not generally utilized in agriculture but were raised by the wealthy for racing or war. Likewise, beekeeping was also vital to sugar production. Some Romans even kept snails as a luxury cuisine.

Pastoral Husbandry in Ancient rome

The land allocation had little effect on the round under pasture. Farmers considered the common pastures to be the state’s property, not the clanship.

It used them partly for its own flocks and herds, which were intended for sacrifice and other purposes.

They were also always maintained using cattle fines, and it granted cattle owners the opportunity of driving their cattle out onto common pasture for reasonable fees.

The legitimacy of pasturage on the public domains may have originally had some de facto relationship to land possession.

But no de jure connection could ever have existed in Rome between specific hides of land and precise proportional usage. This was because the property was acquired even by the metoikos.

However, the ability to utilize the common pasture was only awarded to the metoikos on an exceptional basis by royal favor.

At this time, however, public land appeared to have played only a minor role in the national economy because the original common pasturage was probably not very extensive.

The conquered territory was most likely distributed immediately as arable land among clans or, later, among individuals.

What is it like to Run a Farm in Ancient Rome?

While the nobility owned Rome’s major land area, they were not always present on the farms. Most landowners hired slaves to manage their lands as they themselves prioritized their primary occupations of senators, generals, or warriors at war.

The wealthy paid a trustworthy freedman to supervise those slaves, manage their conflicts, adequately feed and shelter them, assign fair labor, increase production, and ensure the property was properly cared for.

Similarly, all the slaves were to honor and obey Roman deities to produce crops in an adequate amount.

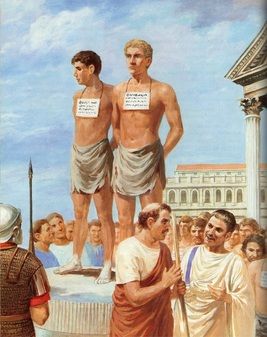

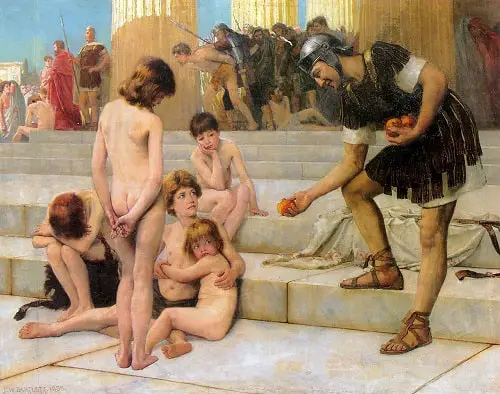

Slavery and Agriculture in Rome

Slaves in Rome were the only or most common source of manpower or labor.

Three basic ways were used to own a slave in Roman civilization. The first and arguably most prevalent method of acquiring a slave was to purchase at the open market.

Romans purchased slaves from merchants in auctions and slave markets, or traders traded them between individual enslavers.

Another method of acquiring slaves was through military conquest, where the landowners brought the captives back from the fights.

The owners then forced the slaves to work on their farms or sometimes sold them to another city.

And the last option to get a slave was from the slave’s family. Any child born to a family of a slave could be forced to work as a slave by the landowner.

Slaves were relatively inexpensive to utilize since they were property. The way they were treated depended on the nature of their owner. Few owners listened to their slaves, and the rest treated them as personal property.

Although open brutality to slaves was regarded as a sign of ill character in Roman culture, there were few restrictions on the penalties that an overseer or slave owner may administer.

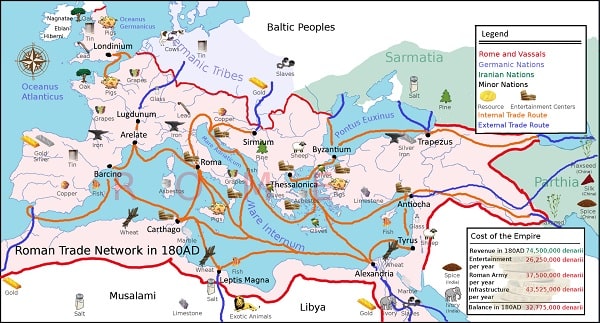

Agricultural Trade

There was an intricate deal of trade among the empire’s provinces. All sections of the empire were economically intertwined.

Depending on the soil type, some regions specialize in producing grains like wheat, emmer, barley, and millet. Others specialized in wine and olive oil.

In his De re Rustica, Columella states, “Heavy, calcareous, and moist soil is not unsuitable for cultivating winter wheat. Barley tolerates no environment other than one that is loose and dry.”

Pliny the Elder also wrote extensively about agriculture in his Naturalis Historia from books XII to XIX, including The Natural History of Grain in chapter XVIII.

The Greek geographer Strabo regarded the Po Valley (northern Italy) as the most economically significant.

He elucidated, “all grains thrive well, but the harvest from millet is extraordinary because the soil is so well hydrated.”

Etruria also had rich soil that was ideal for growing wheat. Additionally, Campania’s volcanic soil also made it ideal for wine cultivation.

In addition to understanding different soil types, the Romans were also interested in what manure was best for the soil. Poultry dung was the best, and cow manure was one of the worst.

Sheep and goat dung was also beneficial. Donkey excrement was ideal for immediate use, whereas horse manure was not suitable for grain crops but was excellent for meadows.

How did Irrigation Support Agriculture in Ancient Rome?

The Romans were skilled at using irrigation to support their agriculture. They used various techniques to bring water to their crops, including aqueducts, canals, and reservoirs.

One of the most famous examples of Roman irrigation is the aqueduct system. The Romans built a network of aqueducts to transport water from distant sources to the cities and towns of the empire. The aqueducts were constructed using a combination of arches, channels, and underground pipes, and they could carry water over long distances and at great heights. The Romans used the water from the aqueducts for a variety of purposes, including irrigation, public baths, and toilets.

In addition to aqueducts, the Romans also used canals to bring water to their crops. Canals were used to divert water from rivers and streams to areas where it was needed. The Romans also built reservoirs to store water for later use.

Irrigation was an important part of Roman agriculture, as it allowed them to grow crops in areas that otherwise might not have sufficient water. The Romans were able to increase their agricultural productivity through the use of irrigation, which contributed to the success and prosperity of the Roman Empire.

Farming Problems

Farming in Ancient Rome faced several challenges. One major problem was the lack of suitable land for agriculture. Much of the land in the Roman Empire was rocky or mountainous, making it difficult to cultivate crops. As a result, the Romans had to rely on terracing and other techniques to use the limited arable land available.

Another challenge was the labor-intensive nature of farming. The Romans relied on manual labor to cultivate their crops, which was time-consuming and physically demanding. In addition, the Romans did not have access to modern machineries, such as tractors or combine harvesters, which made farming even more labor-intensive.

The Romans also faced the threat of natural disasters, such as droughts and floods, which could devastate crops and reduce agricultural productivity. In addition, pests and diseases could also damage crops, reducing yield.

Despite these challenges, the Romans overcame many of them through their innovative farming techniques, such as irrigation and crop rotation, and their use of trade to import food from other parts of the empire. Farming played a vital role in Ancient Rome, contributing to the prosperity and success of the Roman Empire.

Conclusion

It has been speculated that there were no more than a hundred practical experts in the science of geometry at any given time during the Hellenistic period or the Roman Empire.

Furthermore, possibly several thousand committed medical professionals.

On the other hand, people with agricultural expertise would have made up the vast bulk of the 60 million people surrounding the Mediterranean at the time.

Although few would have mastered all skills and knowledge, most would have known how farmers did things from everyday experience in a farm-filled landscape.

Moreover, when it comes to homesteading, Xenophon even stressed the seemingly mundane but essential point that agronomy was separated from other forms of science precisely by being so prevalent and easily accessible.

Farmers’ skills and flexibility in an ever-changing environment ultimately allowed them to feed their families.

It was also farmers at the base of everything that allowed the formation of agricultural traders and markets.

Not to mention, agricultural environs also impacted governments and allowed the nourishment of the great ancient cities.